What follows is a socio-cultural accented analysis of the formation of King Crimson and the release of In the Court of the Crimson King. By taking this approach, I am not wishing to replace an aesthetic narrative with a social deconstructivist one. Rather, it is seen as complementary; as a way of constructing systems of intelligible relations capable of making sense of sentient data. It does this by attempting to ‘recreate’ the social space of the day, the individuals who occupied positions within it and the nature of their relations. This approach, it is suggested, is more reassuring than a Hörderlinian belief in the miraculous virtues of talent and pure interest in pure artistic form; and instead seeks to put in place a reflexive understanding of the necessity of the creativity impulse immanent within trans-historic fields as actualized here in one particular cultural historic period.

Elements of Methodology – Constructing the Aesthetic and its Representation

The approach I have used is to analyse cultural activity as a relationship between individual disposition – personal background, sensitivity, etc. – and social environment, both material and socio-cultural. It is based on Pierre Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice. Philosophically, key to this method is the relationship between what can be called the subjective and the objective. Bourdieu at one point refers to any ‘opposition’ between the academic traditions of subjectivism and objectivism as being ‘the most fundamental, and the most ruinous’ (1990: 25); as different modes of knowledge. It is therefore necessity to go beyond them whilst preserving what has been learnt from each. King Crimson cannot be reduced to simply an empirical, subjective phenomenon any more than an objective, social construction: we need an approach that goes beyond both – as subjectively authentic in its existential representation whilst being open to interpretation in terms of objectively recognised influences that have some general applicability. For Bourdieu, this synthesis of oppositions, which he aims co-terminously to break from both, is achieved through a consideration of structure as a base generating principle. As Isaiah Berlin stated it, ‘To understand is to experience structure’. But, structure in what sense?

For Bourdieu, the basis of science is the simple fact of a coincidence between an individual’s structural connection with both the material and the social world. Everything lies in this connection: here are the structures of primary sense, feeling and thought – the intensional (sic.) links that are established between human beings and the phenomena – both material and ideational – with which they come in contact. This is a basic phenomenological precept; the ‘s’ here intended to draw attention to this structural relationship. Everything we know about the world is both established and developed as a consequence of individual acts of (psychic) perception, which are by their very nature structural because they are essentially relational. However, such structures also have defining generating principles, which are both pre-constructed (coming from the past) and onward-evolving (futures-orientated) according to the logics of differentiation found within the social universe. In other words, the generating principles do not exist in some value-free, Platonic realm; rather, they are the product and process of what already-has-been – values which serve the status quo and/or emerging social forms, and to which individuals converge and/or diverge. This phenomenological structural relation is, therefore, also a product of environmentally structural conditions, which offer objective regularities to guide thought and action in ways of doing things.

The objective and subjective bases to Bourdieu’s theory of practice can therefore also be understood as ‘culture’, as being both structured (opus operatum, and thus open to objectification) and structuring (modus operandi, and thus generative of thought and action). In the case of King Crimson, we see these structures as the relationships formed with individuals and environments, and the values which underpinned such relations, and in the structuring acts of creativity – literally, writing music and lyrics (which also can be understood in terms of their structured properties and the values they convey). Ultimately, the task is to understand the content and form of the (structural) relationships between these different foci: the individuals involved and their personal (cognitive) profiles, surroundings (social and material) environment, and the body of work emerging from them.

This methodological intent can also be seen as a series of philosophical ‘breaks’: from empirical knowledge (events which speak for themselves); from phenomenological knowledge (subjective dispositions); from structural knowledge (socio-cultural determinants); and, indeed, from scholastic knowledge itself (the temptation to form theories about aesthetics, biography, and social forces). These breaks are not a series of exclusions; rather each theoretical position is retained and integrated into an overarching theory of practice. In effect, we need to understand these breaks as implying the addition of a fourth type of theory – reflexive structural knowledge. The key to the integration of the theoretical breaks is indeed the addition of structural knowledge in relationship to the phenomenological, scientific and practical, in order to indicate their essential structural nature. We can say of such structural knowledge, that it arises from practical action – that is the empirical cognitive acts of individuals (including writers, biographers and the subject of their writings) in pursuit of their aims.

We therefore ‘apprehend’ our subject in the practice of apprehending it as a lived act in the same way that their lives are lived – but by a set of scientific, rather than empirical, precepts. The science of understanding lived experience is consequently essentially constructivist (structural constructivism/constructive structuralism) in nature as a reflection of human praxis.

So, we begin with empirical facts of the immediate formation of King Crimson – when and where – and the biographical background of those involved (Level 1).

What then follows is an analysis of the music field into which King Crimson entered: the relational structures of discrete elements within it and the positions held by individuals and agencies (Level2).

Finally, we consider the relationships between this manifestation of the Music Field at the time and the larger field of power (this includes the political field, but also the field of media and commerce) (Level 3).

At any particular time and place, changing structures and institutions can be analysed (an external objective reading) at the same time as the nature and extent of individuals’ participation in it (an internal subjective reading). The two distinct social logics are inter-penetrating and mutually generating, giving rise to the ‘structured’ and ‘structuring structures’, which can be objectified and discussed as such in demonstrable relations – between individuals and artistic pursuits.

The world is infinitely complex and it is impossible to represent the totality of complexity (see other analyses that take different approaches: philosophical, psychological, and spiritual). Yet, faced with this multidimensionality, there are various ways of tackling it. A positivist ‘theoretical’ approach, held to be most robust and ‘scientific’, seeks to extract, simplify, and hypothesise on the basis of findings, which can then be tested against further data analyses. However, our approach takes a different course; one which begins with the totality, accepts the complexity and seeks to identify and explain organising structures within it with reference to their underlying generating principles. Such principles can be consciously, functionally operative at the same time as being misrecognised. The point of the study, then, is partly to ‘unlock’ their misrecognition in order to identify the way they work. Two of Bourdieu’s key conceptual terms in doing so are: field and habitus, each of which exists in ‘ontological complicity’ with the other. Habitus for KC members is their biographies and consequent dispositions, as well as what they took into life in terms of knowledge, skills and experiences; Fields are the particular social contexts in which they find themselves – for example, education, the media, politics, commerce, entertainment – and the identifiable values/ principles which exist within them.

To elucidate…

Field is defined as the ‘objective’ elements of the social environment, and is defined as:

….. as a network, or a configuration, of objective relations between positions. These positions are objectively defined, in their existence and in the determinations they impose upon their occupants, agents or institutions, by their present and potential situation (situs) in the structure of the distribution of species of power (or capital) whose possession commands access to the specific profits that are at stake in the field, as well as by their objective relation to other positions (domination, subordination, homology, etc.).

(Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992: 97)

In our present context, field examples would be the Cultural and Music Fields in which King Crimson operated from the late 1960s and their links with the Commercial and the Media Fields. This ‘certain point in time and place’ clearly also has its antecedents in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

Habitus, on the other hand, is an expression of individual subjectivity:

Systems of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles which generate and organize practices and representations that can only be objectively adapted to their outcomes without presupposing a conscious aiming at ends or an express mastery of the operations necessary in order to attain them. Objectively ‘regulated’ and ‘regular’ without being in any way the product of obedience to rules, they can be collectively orchestrated without being the product of the organizing action of a conductor’

(Bourdieu 1990/80: 53)

This is the individual social identities of the original band members; their outlooks, dispositions and attitudes shaping choices and actions (both professional and aesthetic).

Habitus and field need to be understood as being homologous in terms of structures that are both structured and structuring, mutually constituting. Social spaces are understood as differentiated, and thus structural in essence.

The intent here is to treat objects of enquiry as relational rather than substantiated; in other words, as a network of dynamic relations rather than things in themselves. King Crimson is not an object, or even a person, but a living dynamic. The challenge is then to comprehend, grasp, seize even, something of the logic of this dynamic in terms of artistic activity; not a causal account but an apprehension. The real is relational: what exist in the social world are relations, which exist ‘independently of individual consciousness and will’. The focus is on these principles in terms of aesthetics – artistic production within a cultural field. Habitus and field are the base tools to create this lens; they are ‘epistemological matrices’ in that they are constituted in the process of socialisation of individuals and lay in the structural generative schemes of thought and action, which are activated in particular social conditions.

Level 1 – habitus – begins with the most subjective as expressed in the individual backgrounds of KC members and the initial songs themselves with a particular biographical focus – aesthetic and socio-historical.

Level 2 music field itself; not only the popular music field itself but its relational structures and consequent activities (and output). This is to provide a structural topology of the cultural field as pertinent to King Crimson. Another analytic tool – capital (symbolic, social, cultural and economic) – is used here to articulate the medium of its inner dynamic of the field.

Level 3 is the connections between the music field and the broader socio-economic field structures: ‘Fields within fields’ to highlight the way various social locales – political, education, media, culture – integrate and interface and are, finally, also mutually influential in how biography unfolds. The structure of the approach might more formally be expressed as a three level field analysis of artistic activity:

Field Analysis:

- Analyze the habitus of agents – the systems of dispositions they have acquired by internalizing a deterministic type of social and economic condition. (the empirical biographies of KC members ; their work and the salient generative themes within it);

- Map out the objective structure of relations between the positions in the music field (the cultural field in Britain in the late 1960s);

- Analyse the position of the music field vis-à-visfield as a whole (the various socio-cultural and commercial fields and the field of power – and the ways they influenced each other).

Level 1

To consider the individual habitus of the original members of King Crimson is to focus on the particularities of biography and dispositions; this as a way of appreciating patterns of ‘elective affinities’ (and dis-affinities) between band members. What is perhaps most striking is congruence and complementarity of place and social origin.

There seems to have be a remarkable ‘coincidence’ of a group of guitarists coming together – ‘of a generation’ – in a relatively small, unremarkable, provincial town: Bournemouth (with its outlying districts – Wimborne (Fripp), Winton (Giles) and Poole (Lake). Other associated members of this group would include Andy Summers (The Police), Gordon Haskell (King Crimson), John Wetton (King Crimson), John Rostill (The Shadows), Zoot Money, and Al Stewart. Most of these came from a lower middle class background, thus affording both cultural and economic resources. Most were educated in Grammar Schools at a time when entry to these depended on distinguishing oneself by passing the 11+ examination. Local culture included seaside entertainment, but this would involve accomplished musicians and entertainers, who various KC members supported, either as backing or support bands. On the seaside, such music involved more than three chords and required a developed sense of musical accompaniment within jazz/ swing styles of the dance orchestras. Typical four-member ‘groups’, modeled in the style of the Beatles would have been the contemporary youth alternative to music that went back to the traditional songs of the 1940s and 50s.

A music teacher such as Don Strike, who had a shop in the Arcade at Wimborne, would have been influential in teaching a certain style since he came from that dance-band tradition; so, developed technique, reading music and practicing sophisticated chordal progressions. Both Lake and Fripp were taught by him. Other ‘jazz’ tuition was also available; for example, Tony Alton (Fripp). There was also a local classical tradition, itself also accessed by Fripp – Kathleen Gartell and the Corfe Mullen Youth Orchestra. Local networking was strong; including a prominent and well reputed music shop such as Eddie Moores.

Listening, and playing, therefore, included a range of styles: contemporary, classical, jazz, modern. Styles and names associated with Dorset-based band members:

Michael Giles: Vaughan Williams; father a violinist on Bournemouth classical Orchestra; Skiffle.

Robert Fripp: The Beatles; Dvorak; John Mayall; Chris Barber; Django Reinhardt

Greg Lake: Pop

Both Fripp and Lake practiced Paganini based guitar exercises with Don Strike.

Already, this represents a rich and diverse cultural capital, strong local social capital, and modest economic capital (guitar lessons cost money!)

A telling statement by Michael Giles seems to sum up the general ambience which encouraged an attitude of musical involvement: ‘ Bournemouth was not like the other industrial cities you know, people living a tough, hard working class life, looking for a way out by being a footballer or a musician…the only reason I’ve been able to come up with as to why we became musicians, was because there was not anything to rebel or fight against. So, it was a frustration not having enough challenge…we weren’t trying to escape…driven by angst or terrible conditions’.

What is noticeable is how quickly Michael Giles, and his brother Peter, became ‘professional’: Johnny King and the Raiders -> The Dowland Brothers -> The Trendsetters. Each step represented a hike in professionalism and musical standards. Social capital again was important: The Dowland Brothers played the Downstairs Club in Bournemouth where they would mix with Zoot Money, Andy Summer and John Rostill (future member of the Shadows). The move from semi-pro to professional, however, came in 1964 through the impetus of local businessman Roy Simon (economic capital) who commissioned market research to find out what young people wanted with a mind to providing it as a commercial venture. The Giles brothers (as the Dowland Brothers) joined the Trendsetters who, as well as touring their own music, were ‘good enough’ to back an established international group like The Drifters without ever making the break-through.

Out of that ‘failure’ came the drive to re-found the group by auditioning for other players, which is when Fripp joined to become Giles, Giles and Fripp.

Meanwhile, Fripp’s school friend and fellow guitar student, Greg Lake was working through his own range of pop bands: Unit Four, The Time Checks, The Shame, the Gods.

Against this provincial, musical heritage, can be set a more London-based ethos.

Firstly, Ian McDonald who was born in Osterley, Middlesex, and latterly lived with his parents in Teddington, London. Some of his upbringing would involve a similar jazz/ dance band musical legacy: his parents played Les Paul, Guy Mitchell, Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald. But, also classical – Rimsky-Korsokov, for example (cultural capital).

He played a little guitar and drums. However, unsuccessful at school, he left to join the army, attending the Royal Military School of Music from 1963, where he learnt compositional and arranging skills (academic capital).

On leaving the army in 1967, he plunged into ‘flower power’ London, specifically the Middle Earth Club in Covent Garden (avant garde culture) where he met and worked with Judy Dyble who was then lead singer for folk-rock group Fairport Convention. He also auditioned to work with Peter Sinfield’s band Creation.

Sinfield was also born in London – Fulham – by grew up in an altogether more bohemian atmosphere of English/ Irish parents. His mother was bisexual and the family had a German housekeeper with experience as a Circus performer. As an only child, he was taken into an exotic world of adults; itself also enhanced with his induction into the romantic poetry and prose of Sitwell, Blake, Gibran, Blyton and Shakespeare by his tutor John Mason (cultural capital).

He therefore was steeped in ‘Englishness’ but with exotic flavourings: his professional itinerancy (computers, travel agent, market stall holder) matched by his travels, which took him to Spain and Morocco at a time when the hippy fashion favoured Asian cultures.

Sinfield was more of a poet than a musician – he claims KC was actually born when Ian McDonald finally confronted him with his lack of musical skills but literary talent. A talent that was complemented by a natural feel for technology and the use it could be made of in enhancing performance; for example, in lighting.

It is worth tracking the various social movements that took place as a precursor to the formation of KC1:

- Peter and Michael Giles advertise for other musicians in the light of lack of success with the Trendsetters – Fripp joins (known from the local Bournemouth scene).

- Judy Dyble (Fairport Convention) joins GG&F, or rather they join her in the light of lack of success. With Judy comes Ian MacDonald (Dyble’s boyfriend).

- With MacDonald comes Sinfield (fellow band member).

- MacDonald and Dyble’s relationship breaks down; she leave (musical differences).

- GGFMaC continue: Peter Giles leaves (or is asked to leave). Greg Lake joins (Fripp’s school friend and fellow guitar student).

It is also worth listing the various musical styles that would have been strongly represented in KC1, as predominantly:

Classical: Giles, McDonald, Fripp.

Jazz/Dance: Giles, Fripp, McDonald

Pop: Lake, Giles

Folk: McDonald (Dyble),

These fairly conventional musical styles would have been underpinned by a strand of psychedelic experimentation, mixed with Irish lyricism and Asian exoticism.

Sinfield gave the name King Crimson to the group, or rather this name anointed itself on these five young men and the musical vision they were beginning to articulate. It seems the voice interpolated, or hailed, them, and was almost fully formed when it was articulated.

Of course, all this is being played out in terms that are often personally hurtful: relationships break up (McD/Dyble), musical collaborations dry up (GG&F), band members become out of step with the direction the music is taking (Peter Giles). Moreover, it is taking place in a socio-cultural structure, which includes clubs, musical journalism, the media and parallel musical associations. For example, future KC member (and Fripp school friend) Gordon Haskell is a member of Fleur de Lys with connections to both established groups (The Animals) and stars-to-be (Hendrix). The departure of Peter Giles comes as GGF&McD appear on the BBC programme Colour Me Pop, which itself is a follow up to another appearance on the BBC Radio with Al Stewart – Bournemouth stalwart and pupil of Fripp – and guitar experimentalist Ron Geesin.

It is next necessary to consider the music field as a whole.

Level 2: Field Conditions

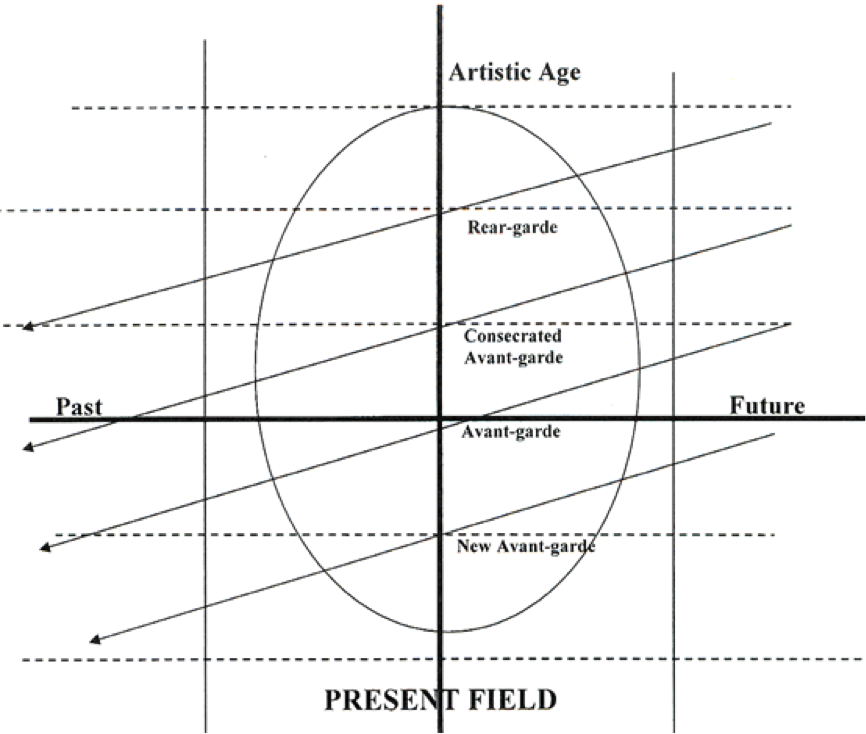

At one point, Bourdieu writes that, ‘To impose a new producer, a new product and a new cultural style on the market at a given moment means to relegate to the past a whole set of producers, products and systems of style, all hierarchized in relation to their degree of legitimacy’. Cultural trends are seen as generational, not in terms of actual age (although age is one determining factor) but in cultural relevance and thus ascendency. The crudest example would be fashion: as established styles are challenged and replaced by new styles the former instantly becomes ‘old’, ‘outmoded’, even irrelevant. This is so for all ideational and cultural products. However, some manage to hang around and exist within the cultural field as ‘consecrated’ forms: in other words, as recognized as formal points of reference or legacy. This is expressed in the diagram below. Generations needs to be seen as moving from bottom to top; individuals as moving and existing on points along the diagonal lines. The ellipse is currently what is recognized. Individuals at the upper part of the diagram – especially the ‘rear garde’ – have an established position: for example, in painting this would include artists such as Rembrandt and Constable. They hardly move at all, therefore, on the diagonal line. This is less so for the Consecrated avant-garde and the avant garde, where there is the risk of any one individual moving outside of the ellipse; and even more so for the new avant garde where profile can be very transitory. The new avant garde is a very unstable position and there may be any one individual who is very prominent ‘in the day’ but disappears quickly as the generation is displaced by a faction within it.

Once established as an avant garde, therefore, any cultural movement is susceptible to be displaced; indeed, has to be by the very logic of the field.

The diagram is an attempt to offer a graphic of the dynamic the cultural field of production, of which the music/ folk field is one manifestation. It demonstrates one possible way that artistic generations relate to each other and, indeed, the possible destinies of individuals who pass through the cultural field. It is predicated on six sorts of time. Firstly, there is actual time with a past, present and future. Secondly, these are accountable in terms of recognised dates: days, weeks, months and years. Thirdly, there is individual time: that any one person is born at one time and dies at another. Fourthly, is the presence of any individual in the cultural field – inevitably linked, if only by association (or indeed, non-association), with a certain state of the field at a specific time and place. Fifthly, is the recognised position of individuals at a point in time within the field. Sixthly, is the acknowledged significance of a particular individual or group within the field and across generations and their journey through them. The diagram is therefore conceived as in flux, with a movement from bottom to top, with everyone – individually and/or as part of a group – acting for recognition, and thus valued value, within the field.

One further aspect of the ellipse diagram is that both between and within generational lines, time differences can expand and contract: years may pass by with little generational distinctiveness, or may contain many movements and sub-movements in a short period of time. Individuals may also be able to operate with a degree of inter-generational lassitude, or be closely defined according to a particular point in time. It is in the nature of the diagram that at a time of dramatic change – the arrival of the punk movement in the 1970s for example – changes in artistic practice are very time sensitive: someone ‘might miss the boat’ by being out by a few weeks or months.

Bearing all this in mind, we can see King Crimson as very much announcing a new avant garde, and so would be placed in the vanguard on the bottom diagonal line of the diagram. Also, along this line for the period would be (with dates of inception): Roxy Music (1971), Emerson, Lake and Palmer (1970), The Nice (1970), Yes (1968) and Genesis (1967) – (these dates are notional). Subsequently, this generation was given the title ‘progressive rock’; although, clearly, they do differ considerably from each other. Indeed, many of the musicians within these groups took the form, if not the content, of King Crimson is defining themselves – in fact, many of them shared the same individuals or had previous (and future!) associations (for example, Bryan Ferry of Roxy Music auditioned for King Crimson).

In this case, the ‘avant garde’ would be: The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Cream, The Who, Bob Dylan, etc.

The ‘consecrated avant garde’ would be: Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, etc.

The rear garde would be: Perry Como, Connie Francis, Vera Lynn, David Whitfield, Dickie Valentine, Alma Cogan, Ronnie Hilton, Doris Day, Paul Anka

This theory of avant garde also suggests that the new generation can establish itself more by a transmodification of what exists rather than a genuine ‘new’; novelty is not innovation. The eventual power of the avant garde member to become consecrated probably rests on this distinction. However, if something is completely new, it is unlikely to be recognized at all. An avant garde therefore has to have enough in it for the would-be audience to recognize, but served up in a way that appears new; again, a triumph, very often, of form over content.

King Crimson in 1969 had a large ‘paintbox’ as described above, with elements of experience rooted in Jazz, Folk, Classical and Pop. However, it combined them in a way that also referred back to something much more ancient and indeed quintessentially English: Pastoral, Epic, Melancholy, Narrative, Magic. The energy infusions of jazz and pop/rock warded off temptations of extreme whimsy and indulgence: this was a professional band with high standards (gained from previous experience) of musicianship. All members had worked in semi-professional groups: dance bands needed a job doing, and players were expected to provide it; The Trendsetters, after all, recorded for Parlophone – the record company of the Beatles. As Lake commented, ‘everything was tight, every one knew if what you played was not ‘right’’.

This level of focus is congruent with Bennett’s view of creativity; where a lot of conscious energy had been put into the preparations – the previous years. Now, it was time to unleash the creativity.

Returning to the diagram above, however, any band would still need backing/ support: financial, networking, symbolic, and cultural; what Bourdieu calls Economic Capital, Social Capital, Cultural Capital and Symbolic Capital.

What is Capital? I use it to describe the medium of social dynamics within a field – its sociogenetics. For Bourdieu, positioning in social space is defined by both the quantity and configuration of capital anyone retains. All capital has value – in other words, it ‘buys’ advantage by position in social space by being recognised as being the currency, which fuels its operations. Clearly, different forms of capital feature more than others according to the activity of the context: so, what ‘buys’ position (recognition) in the drama field might not be the same as in music fields, whilst some might indeed overlap as these two are very close in the cultural field overall. In this century, there would be a larger difference in capital type as valued between the scientific field and the cultural field. All capital has ‘symbolic value’, however, and much of it ultimately leads to procurement of economic capital (money wealth). There are, therefore, four basic forms of capital: symbolic, economic, cultural and social. To add to the two already described, social capital is the networks of social relations anyone has access to, and can be mobilised to gain entrée within and around the field context. Cultural capital, furthermore, relates to any cultural product – personal style/ taste, education, or objects – held by an individual. This might be membership of certain prestigious clubs – which, again, would also imply further social capital. As noted, capital is governed by rules of quantity (the more the better) and configuration (one form in relation to another). This is a useful tool of analysis, as it helps us to navigate within social – field – structures, to show up how their activities are defined and driven by attempts at capital conversion, acquisition, and deployment. I shall therefore employ the various capital types en passant as descriptors at various points in my discussion below; this, in order to draw attention to the way symbolic, economic, social and cultural aspects of the artistic environment play with and off each other in the processes of socio-cultural evolution.

King Crimson certainly had social capital (networking), as evidenced above. Initial financial backing (economic capital) was provided by the Hunkings – Angus and Phyllis. Phyllis was the sister of McDonald’s father (social capital) and married to Angus – a Northern industrialist (old, consecrated capital). Culturally, however, they also aimed high. As Giles, Giles and Fripp two KC members had already established a relationship with Decca by going directly to the top man (Hugh Mendl) (symbolic capital). This meant that social connections were already there to be drawn upon: from producer Wayne Bicherton (who played with ex-Beatle Pete Best) to Tony Clarke, producer of the Moody Blues (who were gaining a high level of prominence in the 1968/ 69) period (symbolic/ cultural capital). In effect, one strategy of new avant garde is to associate with the old one in order to make the break with it all the more evident. Clearly, there was resonance between the Moody Blues and King Crimson, not least in the use of the mellotron to similate the sound of string orchestras. KC worked with Tony Clarke but then abandoned the recording – a kind of prise de distance – when it became clear that the latter dispositionally was turning them into Moody Blues mark 2.

Capital acquisition – social, cultural and economic – requires investment of the relevant resources. KC had made the right moves: knew (some of the) right people (social capital), procured funds (economic capital), and established a line-up with recognized experience (cultural capital). They also did the rounds – in London (the centre of the cultural universe – strong symbolic cultural capital) – of the clubs with reputation (symbolic capital) within the music (rock) field: for example, the Marquee and Speakeasy, which brought them into contact with individuals with existing capital holdings in the field). All this established their position within that field by recognition: acknowledged value by others with ‘the power to speak’ – other musicians and journalists. This symbolic capital paid off with a live concert in Hyde Park where they were on the line up to support the Rollings Stones. What better symbolic display than for the old and the new avant garde to line up against one another. Apparently, KC blew the Rolling Stones off the stage; although this was never going to seriously undermine the latter as rock deity and therefore beyond displacement (consecrated avant garde). Not quite a ‘royal flush’ for KC but very near it!

A further note with respect to the cultural field is the way various capitals are characteristic of certain groups; in particular, the avant-garde. So, for example, large-scale mass cultural products may accrue high monetary profits, but carry with them little cultural capital due to their popular appeal (lack of scarcity). Whilst the opposite is also true: small-scale, restricted market orientated goods may have little financial return but still possess high cultural capital due to laws of raity and distinction: ‘art-for-art’s-sake’ is the typical stance of those producing at this level. So, the field of cultural production is itself subdivided by the field strategy adopted by producers: large-scale and popular (CE+ = high economic capital) or small-scale, restricted production (CC+ = high cultural capital). These juxtapositions between large-scale production (common e.g. pop music), and, small-scale production (rare e.g. bohemian folk), generate (and are generated by) structures within the field.

As a field strategy and positioning, everything about KC in 1968/69 orientates them towards a large scale, mass production. The disposition to do this had partly been gained by doing the opposite: the collective experience of small-scale, restricted production. In brief, the band had individually gained professional experience to know the field and what mattered, what was valued in it, and who were the gate-keepers. These field manoeuvres were at a time when the previous avant garde appeared decadent, even exhausted. This and the internal chemistry of the band produced a unique hybrid of styles, which meant that history and art were on their shoulders. Everything lined up: psychology, history, philosophy, aesthetics, culture, the spiritual. The voice of In the Court of the Crimson King became a necessity, and, locally, the band members had the individual and combined functional capacity to actually manifest it. As if the music just flew in through the windows, all they had to do was just ‘pluck it out the air’ – they could do no wrong (for a time at least!).

In my next and final level, I consider the broader socio-cultural context of 1969 and the place of the cultural field (and music field) within it leading up to and during the creation of In the Court of the Crimson King.

Level 3

Fields within Fields – The Music Field and the Field of Power – 1944 -1969 – the World at Large

This section is intended to examine the relationship between the music field itself and the ‘field of power’ as a way of understanding how King Crimson in 1969 positioned itself within the social space of the times and the influence it may (or may not) have had on them. Really, the ‘field of power’ includes everything else – politics, commerce, the media, education – in order to show how these impact and impinge on the field under consideration – here the music/ rock field of the late 1960.

Towards the end of this section, I set out, in some detail, an analysis of the general socio-political conditions of Britain in the 1950s and 60s – the formative years of the members of KC1. Briefly, this period typified itself socially as ‘post-war’, and as one of industrial decline and decolonialisation. At the same time, it takes in the explosion of culture – in all shapes and forms – of the 1960s (mostly delineated by The Beatles’ first and last LPs – Please, Please Me and Abbey Road). These were years of exuberance, on the part of the younger generation at least. And yet they were also politically troubled years, including war, assassination and civil unrest.

The music of King Crimson was clearly not a politically orientated; say, in the way that Folk music was. And, it is arguable that they took inspiration from worlds – both musical and literary – prior to this period, albeit hybridized into a new, contemporary avant garde form. Nevertheless, King Crimson could not be politically (with a small ‘p’) neutral since they entered a cultural field, the power dynamics of which included fields, which operated closely within power relations with each other; for example, commerce, the media, etc.

There is some evidence that the music/ rock field itself was undergoing enormous change in the 1960s. Fields work to establish their autonomy; the dynamic of their change is also often driven by fast expansion in size. Both were true for popular music in the 1960s, as a new generation had the time, and money, to buy records and attend clubs and dances. This trend began much earlier in the century and was driven by technological changes as well as changing social habits.

Traditional cultural habits in the nineteenth century juxtaposed ‘high’ with ‘low’ culture along social class lines; the ‘cultured’, educated, middle classes attending public performance based on the classical music canon, whilst working classes relied on pubs, the music hall and their own resources for entertainment. This would be in an age before mass communications. Increasingly, this situation changed in the twentieth century: from the 1930s and 40s the ‘picture house’ (cinema) increasingly replaced the Music Hall as the popular site of entertainment which, as somewhat of another cultural ‘Trojan Horse’, brought American themes and stereotypes into the lives of everyday Englishmen and women. Records – phonographs – were at first used as straight recorders (in field collection and the spoken word, for example), but increasingly were marketed to the general population. The war years gave the radio a boost as a live communicator of events, enhancing the BBC’s profile as a major provider of news and advice to the people of Britain. The radio was then in turn eclipsed by the television in the1950s. In fact, there is a significant evolution and the graphs for attendance in various forms of entertainment demonstrate a chiasmic structure: an inverse parallelism. So, between 1954 and 1962, radio-only licenses went from 10 million to 2 million, whilst combined TV/ radio licenses rose from 2 to 10 million. Meanwhile, attendance at cinemas, which in the past had taken trade from the music halls, dropped from 1300 million to 300 million during the same period. Records had varied in size – 7 inch, 8 inch, 9 inch and 10 inch – in the 1930s and 40, and many homes had a collection of 78s shellac discs – the speed at which they were played – before settling to the 7 inch 45 rpm and 12 inch 33 rpm in the 1950. Top selling popular records in the 1950s were invariably show/ film soundtracks or recordings of the so-called ‘crooners’ – Frank Sinatra, Gene Martin. Lonnie Donegan’s topping of the best-selling LP charts in 1956 (‘the year that Britain changed’ according to Beckett and Russell) represented a perfect hybrid of the old (folk/ballads) and the new (rock n’roll/ jazz). In terms of singles, however, the charts were still dominated by individual singers: although the established singers of ballads – Perry Como, Connie Francis, Vera Lynn, David Whitfield, Dickie Valentine, Alma Cogan, Ronnie Hilton, Doris Day, Paul Anka – were somewhat eclipsed in terms of best sellers by younger – Elvis Presley, Frankie Lane and Guy Mitchell. Elvis Presley and Chuck Berrywere evidently not dance band. But, the changes of the 60s with its focus on groups swept away both and the previous musical generation as the focus of pop/ rock music for a teenage audience.

As noted above, members of King Crimson had experience of playing for the dance bands and backing established names in popular song. Some also had experience in 60s style ‘beat groups’ who rode the wave set out by the Liverpool bands. Ironically, 60s bands were themselves taking inspiration from American singers – blues, jazz and soul – to which they hybridised, repackaged and gave a modern style (although this was not always clear to the teenagers who followed them).

We can also see differences even in the choice of musical instrument and the place it held in cultural activity. Up until the 1950s, the standard instrument for the working class was piano or piano accordion (cultural capital), and it was not unusual, even amongst relatively poor social groups, for families to have one. But, by the 1950s, the guitar increasingly became the instrument of pop culture. Elvis played a guitar, indeed many the modern American singers did; an approach and style that somewhat eclipsed the model of singer with backing orchestra, which had been the dominant form up until that point. In Great Britain, the ukulele was a cross-over instrument and skiffle bands in the 1950s utilized it, along with guitars and tea-chest bass in the rising aesthetic of the popular musical art form. So many individuals, who later established themselves in the folk and rock music fields went through skiffle bands, including Mike Giles and John Lennon. Both the ukulele and skiffle provided small, relatively inexpensive ways of making music.

The mellotron, utilized to such powerful effect by King Crimson, along with the Moody Blues (not to mention The Beatles and a host of other contemporary rock bands), began life as somewhat of a replacement for a string orchestra in dance hall situations. Unlike the organ, it could simulate actual strings and wind instruments; although, of course, the way it was used was highly customized for the popular musical rock vernacular, which was a long way from straight orchestral accompaniment. This is another good example of how not only musical tropes, but instruments themselves, can be redefined when an avant garde is constructing itself. So, the jazz/rock guitar of Fripp, mellotron strings of Giles and wind instrumentation of Ian McDonald can again be seen as having its antecedents in classical, jazz and folk guitar styles – this time relayed in an upfront amplified, electrical mode.

The General Condition – Britain in the 1940s-50s-60s

Books on the 1950s and 60s refer to the spirit of the times: Having it So Good and White Heat describing the socio-political mood of Britain during these years. The author of the former – Peter Hennessy – has also written a book on the 40s – Never Again – which also shows up a predominate sentiment of the time, whilst war was still a recent memory. But, it is perhaps the title of another book by the same author – Never Had it So Good – that best draws attention to the ambiguity that Britain was caught in for many of these years: on the one hand, liberating itself from the past and preparing itself for the ‘swinging sixties’; but doing so whilst still holding on to a number of traditional sentiments, beliefs and cultural icons. Such can be identified by simply looking at the trends of General Elections from 1945-64. The shock of the first post war election in 1945 was that Winston Churchill was heavily defeated when the Clement Atlee and the Labour Party gained a 146-seat majority in Parliament. The reasons for this apparent shunning of the man who had brought England through the war to victory are varied and complex, including punishment for the Conservatives for having got Britain in the war in the first place (!), as well as the fear of returning soldiers that they would be treated no better than their counterparts after the First World War, many of whom were left damaged and destitute. The Labour Party’s promise of full-employment based on Keynesian economics as well as the establishing the Welfare State was also an attractive platform. Nevertheless, the next election in 1950 resulted in a reduced Labour majority of just five seats. By now, the Conservative did not oppose either Welfare State or Nationalisation, although disputed the extent and speed of the latter. The relative collapse of Labour is somewhat apparitional since their percentage share of the vote went down from 47% to 46% only – but a range of constituency changes disadvantaged them. Labour subsequently decided to go to the country yet again in 1951, hoping to increase their majority but, despite gaining the most votes, lost to the Conservatives (the second of three twentieth century elections where this was the case). It also marked the return of Winston Churchill to government and the beginning of the so-called ‘thirteen years of Tory Rule’ until the Labour Party won next in 1964; the Conservatives winning in both 1955 (under Anthony Eden) and 1959 (Harold MacMillan). MacMillan 1957 stated, “Let’s be frank about it, most of our people have never had it so good. Go around the country, go to the industrial towns, go to the farms, and you will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime – nor indeed ever in the history of this country. What is beginning to worry some of us is, ‘Is it too good to be true?’ or perhaps I should say, ‘Is it too good to last?’”. Of course, the answer to both questions was/ is ‘yes’: it was both too good to be true and it was too good to last – the ‘having is good factor’ was indeed somewhat of an illusion. Nevertheless, the catharsis of World War victory along with the Welfare State and Nationalisations led to a time of contentment and apparent progress. In 1953, the target of 300,000 ‘people’s houses’ had been built under the policies of Harold MacMillan; council sponsored accommodation with inside toilets, modern facilities for families to replace dereliction. The Clean Air act was passed in 1952 resulting in a gradual disappearance of the famous industrial killer smogs. By 1955, just 1% of the workforce was unemployed. The generations I describe in previous sections were not living hand to mouth for existence: there was social concern and leisure practice that only emerges from material surplus. An expansiveness, in all forms of life, was creating a prelude to the revolutions – communications, sexual, artistic – that were waiting to explode in the 1960s. Yet, economically, the picture is one of contingent decline and neglect, and lack of competence, if not incompetence, to do anything about these. The war had shrunk the British economy and necessitated the giving up of economic advantages – for example, the liberalisation of trade barriers and capital flows to the USA as the latter sought to capitalise on the loans it had provided for post-war reconstruction. The new economic power that the USA exerted directly weakened the British economy; so much so that when convertibility was due for introduction in 1947, what followed was a Sterling crisis as it slowly lost value on the international exchange markets. Put bluntly, as living standards rose, the Welfare State was constructed, and industries were nationalised, the costs of war, loss of colonial markets, and industrial sluggishness (many struggled to meet national and international demand) impacted negatively on the economy. Then, when other countries seriously damaged by the war reconstructed – France, Germany, etc. – they too reclaimed their position in world markets, which further undermined the scope of the British industries. Basically, there was just not the tax revenue to support the levels of spending to which the government had committed. The economy stuttered, inflation rose rapidly, economic growth declined to half that of Germany and France, and industrial relations worsened as workers in the new nationalised sectors opted for higher wages rather than social solidarity. Meanwhile, education and training retracted. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to judge, and a certain sense of community had survived from the war.

Yet, one national illusion after another was being shattered at this time: of being a colonial power, the centre of the world, victorious, and ‘in charge’. But, this was never a black and white affair. Just as economically, Britain acted as if it was rich whilst actually it was quite poor, so internationally it postured a key political profile whilst its actual influence was contracting. For example, it became the third country to develop a nuclear weapon in 1952, whilst its actual international influence reduced considerably through loss of empire. Its would-be prominence was eclipsed even more by lack of economic resources, although it still managed to commit over £32 million to Atomic Energy in 1951/52. Further Hydrogen bomb tests were carried out in 1957, a year after the Suez crisis when Britain joined in an invasion of Egypt along with France and Israel in order to regain control over the Suez canal and remove the Egyptian President Nasser from power; only to have the USA, Soviet Union and the United Nations force them to withdraw. Symbolically, it was a defeat for Great Britain, not just over Suez, but as a world power. ‘The Bomb’ also crystalized opinion around fear of nuclear war and mass destruction, which itself was intimately part of the Cold War and the establishment’s fear of the communist Soviet Union. However, Britain avoided the excesses of McCarthyism – partly, at this time at least, because it was (is?) a very elastic and hierarchical country and more stable with its constitutional monarchy than the American case.

Britain was caught in this strange position between success and failure, the past and the future, which was often translated culturally as ‘the young’ and ‘the old’. Everywhere these oppositions only became more accentuated as the 1950s and 60s moved on. This characteristic can indeed be identified in the way Britain voted Winston Churchill back in in 1951 after having voted him out in 1945. The style of government he represented, somewhat accentuated by the Conservatives embracing of the Welfare State and the cause of nationalisation, was patronal, patriarchal and elitist. Most of the Cabinet, after all, were ex-Etonians and, of course, male. Churchill – partly perhaps through the experience of war and his advancing years – was by then a consensus politician, seeking social and industrial peace at all costs. Operation ROBOT is a good example of this (the acronym stands for the initials of the three civil servants who devised it – ROwan, BOlton and OTto Clarke – under the Chancellor Rab Butler). In the face of a worsening balance of payments account and a run on gold reserves, the plan proposed the type of liberalisation that Britain would have to wait until the Thatcher years of the 1980s to finally get. If it had been implemented, the exchange rate would have been floated allowing Sterling to find its own value: the logic being that exports would become cheaper, stimulating industrial output, and imports more expensive, discouraging excessive dependence on overseas markets by making them costlier. In a way, it advocated a liberal style of restructuring as ‘un-economic’ industries would consequently be priced out of the market. So, food prices would rise along with inflation, thus living standards fall, and unemployment increase possibly to over one million. Exposure of Britain’s industries to the logic and profitability of world markets would have required discipline to see through – as with Thatcherism – but the end results, it was argued, would have been justified. It would also, of course, have ended the ‘new deal’ spirit, which had united the country in the years, which followed victory in the Second World War. With hindsight, it may be argued that this is precisely what Britain needed to bring its economy into the twentieth century and, putting it off, was most costly, making the eventual Thatcherite course of actions in the 1980s all the more painful. Some in Churchill’s Cabinet – for example, Lord Cherwell the Paymaster General – argued, however, that it would be political suicide; especially to a Conservative government with a small majority. Certainly, the degree of resultant industrial unrest would have been substantial. In the end, Churchill and his government rejected the plan, allowing Britain, some would argue, to go into the future by continuing to live in the past. In effect, Churchill chose consensus and social care over economic imperative. Whatever the rights and wrongs of this position – and there are many on both sides – we might see this decision as his final ‘gift’ to the nation, allowing it to party a little longer – a celebration that extended to the end of the 60s – before the final day of reckoning arrived.

The World King Crimson

Clearly, the members of King Crimson were born in or just after these war years and became teenagers in the 1950s: But, that decade changed drastically in complexion from its outset to close. Unlike their parents, teenagers hardly knew the austerities and exigencies of actual war and were ready to define their own ‘new world’ in opposition to anything belonging to them. Indeed, war itself became distant and virtual – despite ‘the Bomb’ – allowing for a certain indulgence on the part of teenagers in affirming their distinction from the older generations. As Giles states it, as teenagers they learnt music to distinguish themselves because, in their corner of England, there was little else to kick against. The new world had been announced, somewhat unceremoniously, when Winston Churchill, lost the first general election after the war. Since then, the Tories regained power but, with an expanding communications network, a ‘liberated’ youth and the raising of international cultural barriers had instilled a spirit of the Global village, and with it communal living in the broadest sense; all now seen as a distinct possibility for a new life style. The general election wins of Harold Wilson and the Labour Party in the 1960s might be viewed as part of this combination of youth opposition and optimism; loyalty to the labour movement connected to and cultural progressivism, which reigned for the rest of the 60s.

Field theory suggests all fields move towards autonomy and are ultimately driven by economic capital, converted, as it may be from cultural and social capital. There is some evidence that this is exactly what was happening in the music fields in the 1950s and 60s. However, the way of doing commerce within the field was changing. Records in the 50s had been dominated by a relatively small band of popular singers. The record company would be part of a large-scale corporate agglomerate. However, this was beginning to break down. Elvis Presley and his contemporaries recorded for relatively small companies like Sun to begin with, and it became clear that much commercial viability rested within these companies faced with an expanding youth market ready to invest culturally in the latest sounds.

The realization that there was money to be made in pop culture also dawned on various small-scale entrepreneurs. So, a culturally aware individual like Brian Epstein, who owned a record shop in Liverpool, saw the commercial potential of moving into entertainment management when he signed up The Beatles. He was not alone and other – some music related and other not – regarded the expanding popular music market as a sound business opportunity. So, George Martin also signed The Beatles for Parlophone – a label renowned, up until that point, for recordings of the spoken word. Others made a similar move; for example, the entrepreneur Nat Joseph began to sign up the new folk avant garde (Ralph McTell, Bert Jansch, John Renborne, Pentangle) for his Transatlantic label which, up until that point, was most successful with its records of sex education. Eventually, players themselves, and those associated with them, set up their own labels as commercial ventures: Witch Season (Joe Boyd and Muff Winwood – brother of Traffics’s Steve Winwood) – as a sub company of Island Records (founded by Chris Blackwell in 1962, mainly as an outlet for Jamaican music but now very much representing the new rock avant garde – including King Crimson); Immediate Records (Andrew Oldham – manager of the Rolling Stones); Harvest Records (Norman Smith – the Beatles sound engineer), Apple (The Beatles), Threshold Records (The Moody Blues), . The cultural field therefore became increasingly susceptible to international influences, which themselves opened up commercial potential from the exploitation of overseas markets both in the UK and abroad.

Most of these companies were eventually swallowed up by the big conglomerates: Capitol, EMI and Universal Music (which seems to have ended up owning everything!)

Similar trends can be identified in the commercial management of King Crimson, and its members: a move from small-scale local and individual support to more professional and corporate backing. However, here it is important to understand these trends within a changing field, and one that increasingly involved other sections of the commercial field. Local Dorset businessman Roy Simon took the commercial initiative with the Giles Brothers in 1964 when, after canvassing youth, he went about constructing a group – The Trendsetters – by placing an advertisement in the pop music newspaper the Melody Maker; and he was not mistaken judging by their level of work as backing band and performers of their own music, as well as signing for Parlophone, although not actually making the ‘big breakthrough’. Producer/ manager Frank Fenter also realised there was money to be made; this time, in employing (Gordon Haskell band) Fleur de Lys as studio session musicians rather than a touring band, reputedly making himself 1000 pounds a week, out of which he paid each band member 15 pounds. This continued the established principle of managers exploiting their artists! Also, as noted, KC1 bought its equipment and launched itself with financial backing from industrial businessman Angus Hunking. But, these are individuals looking for business opportunities within an expanding market, but that market itself was becoming increasingly professionally, commercially minded and led, and panoptic.

I THINK THERE IS SOMETHING MORE TO BE SAID HERE ABOUT WHICH I DO NOT ALTOGETHER HAVE DETAILS – IT’S THE WAY THE POP/ROCK MUSIC INDUSTRY RESTRUCTURED ITSELF SO THAT THERE WERE FEWER AND FEWER OPERATORS WITHIN IT – AUTONOMY! – THERE WAS RESISTANCE TO THIS WITH THE INDIE LABELS OF THE 1970s+ BUT, ESSENTIALLY, SUCH CENTRALISATION AND CONSEQUENT CORPORATE CONTROL HAS JUST GOT STRONGER AND STRONGER IN DECADES SINCE. THERE IS MORE INVOLVEMENT WITH THE LARGER COMMERCIAL WORLD – PENSION FUNDS, ETC. AS SUCH, INDIVIDUALS DRIVEN BY AESTHETIC RATHER THAN (OR AT LEAST AS WELL AS!) COMMERCIAL INTERESTS HAVE BECOME FEWER AND FEWER. THEY HAVE ALSO TAKEN OVER ALL LEVELS OF SCOUTING, PRODUCTION, MARKETING AND SELLING BY CONTROLLING COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS – EMI, APPLE, ETC. ‘ART’ THEREFORE BECAME INCREASINGLY AN COMMERCIAL CONSTRUCTION AND IMPERATIVE RATHER THAN A CREATIVE ENDEAVOUR. NOT SO MUCH FOR KC1, 1969, BUT THIS TREND WAS ALREADY EVIENT IN THE 1970S – EG, FOR EXAMPLE.

Bands on the up, of course, take support where they can find it, including Dunlop Tyres. However, clearly, once King Crimson was a living entity, and performing as such, more direct management was needed by individuals who were media literate: enter David Enthoven and John Grayson. Interestingly, these two originated from the Noel Gay Theatrical Agency, and they gave up their job to manage King Crimson showing that they too recognized the commercial potential of pop/rock music – indeed, there would have been plenty of other examples at the time (small but with high levels of symbolic capital (and potential economic capital) within the field). The fact that King Crimson did not at first sign a contract and, when they did, did so on terms that were not the norm, shows how commercial times were indeed changing. Michael Giles: ‘The big difference was that most musicians would rely on record company support in order to get equipment or rent their flat or do something. They were beholden to the record company. The record company then could harness the young men’s energy and give them a small percentage of sales. But, we already had the attitude that we didn’t want to be ripped off by a record company because we’d already done the Decca thing by returning their contract. We already knew that lease-tape deals had been done in the past, so we knew that we didn’t have to sign up to a record company to do what we wanted to do…David and John also realised the benefits of independence’. So, experience in the past allowed the group a certain savvy on what to do and not to do. Enthoven and Grayson then invested further (economic capital) to keep the show on the road hoping, like any judged investment, for a return on their outlay. These sorts of moves are reminiscent of the ‘heroic times’ of the French Impressionists, which is where painters, for the first time, took ownership, and thus control of their art. Art for art’s sake, which reflected the needs of its audience. Music for music’s sake may well have reflected the needs of King Crimson’s potential audience given the socio-cultural climate to the day: post-hippy, pre-punk.

At this point, I wish to set out the post-war period leading up to In the Court of the Crimson King year by year:

1944. 3rd December, the Home Guard was stood down. Nevertheless, hostilities with Germany were far from over: 168 people were killed in the New Cross Road when a German V-2 rocket landed there. Jimmy Page (Led Zeppelin), Roger Daltry (The Who), John Tavener (English Classical Composer), Nick Mason (Pink Floyd), Joe Cocker (singer), Ranulph Fiennes (adventurer), John Entwistle (The Who), Tim Rice (lyricist), Jim Capaldi (Traffic), Roger Dean (artist), Alan Parker (Film Director) and Dave Davies (The Kinks) are born. The following year, the war ended, launching a ‘new start’ for Britain.

This was signaled perhaps most symbolically with the defeat of Winston Churchill at the General Elections, who had led the country through war and to its successful conclusion, in July 1945. The victory of the Labour party led to the setting up of the Welfare State and the nationalisation of industries: Family Allowance, the National Health, Free School Milk, Bank of England, Coal Industry, and the British Railways. The first Comprehensive School opens. The later 1940s can be considered the years of ‘clearing away’ and preparation for the explosions, which would follow. Slowly, the nation turned from present necessity to future possibility. 1946: Robert Fripp and Ian MacDonald are born (Mike Giles, 1942, Peter Sinfield, 1943). 1947: Greg Lake is born.

The BBC began children’s radio with Listen with Mother in 1950, and the Eagle comic first appeared. The puppet Sooty and the Flower Pot Men appear a year later. The first English New Town was built in Corby, Northamptonshire and the first package holidays and holiday camps were opened. The Conservative Party published its One Nation social policy statement and cultural and sporting events increased: figure skating, football, motor racing, ballet.

In 1951, the launch episode of the BBC radio series The Archers is broadcast and Dennis the Menace makes his initial appearance in the Beano. Zebra crossings are introduced. The Conservative Party with their 77 year old leader Winston Churchill returns to power in October with a 17 seat majority in parliament. Trade Union membership reaches a peak of 9.3 million members and the first residential tower block is built.

Princess Elizabeth succeeds to the monarchy in 1952, a year which also saw the UK developing an effective atom bomb, the removal of trams in London, and the end of tea rationing. Great smogs blanket London.

In 1953, Derek Bentley is hanged for his part in murder. Elizabeth is crowned Queen; the first James Bond novel is published – Casino Royale. The Quatermass Experiment – the BBC’s first science fiction series is broadcast, as is The Good Old Days music hall variety show. Italian coffee bars are introduced to the UK – the first being in Frith St, Soho, London. The Johnny Dankworth jazz orchestra is launched. Dylan Thomas dies.

In 1954, just 17% of British households have a TV set, to which is broadcast the 100th Boat race – Oxford wins. Roger Bannister is the first man to run a mile in under four minutes; and Diane Leather is the first woman to run it in under five minutes. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is published. Second Wold War Rationing is at last fully ceased, whilst the first purpose built comprehensive school opens. Winston Churchill becomes the first sitting British Prime Minster to reach the age of 80. Wimpy Bars open and Hancock’s Half Hour is aired by the BBC.

The winter of 1955 was particularly cold, followed by a heat wave and severe gales later in the year. A state of emergency is called when train drivers and firemen go on strike. Polio vaccine is introduced to the UK and 500000 + are quickly inoculated against the disease. The Conservative Party again win the General Election, with Anthony Eden becoming Prime Minster. The last woman – Ruth Ellis – is hanged. The first Berni Inn opens in Bristol. There are significant rail crashes in Milton and Barnes, and the BBC announces the names of its newsreaders. Lonnie Donegan’s Rock Island Line is released. Heroin is criminalised the following year in 1956 – described by Beckett and Russell as ‘the year that changed Britain’. Thousands of new homes are planned to be built on bomb sites in London and other large cities. Double Yellow Lines parking is introduced. The first Premium Bond goes on sale – cost £1 with a potential £1000 jackpot. Third Class rail travel becomes second class. Look Back in Anger by John Osborne is performed at the Royal Court Theatre and John Lennon forms the Quarrymen. The transatlantic telephone link is inaugurated, whilst PG Tips uses chimpanzees in its advertisements for the first time.

Tesco opens. Harold Macmillan succeeds Anthony Eden as Prime Minister when the latter resigns as a result of ill health in 1957. The Cavern Club opens in Liverpool and John Lennon meets Paul McCartney. A rail crash in Lewisham, London, kills 90 people. The Queen’s Christmas message is broadcast for the first time on television. The Andy Capp cartoon character appears in the Mirror. In his summer speech, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan says ‘most of our people have never had it so good’. Bert Weedon’s Play in a Day guitar tutor is published.

Work on the M1 motorway begins in 1958, whilst some 2,500 workers are made redundant when dockyards are closed in Sheerness and the Isle of Dogs. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) organises its first protest march in April, and official Church of England backing is given to family planning. The first Carry On film is released. Cliff Richard’s Move It reaches number two in the charts – reputedly the first authentic rock and roll song outside of the United States. There are race riots between blacks and whites in Notting Hill. Parking Meters are installed for the first time. Donald Campbell sets the world water speed record and computers are shown for the first time. BBC’s sport programme Grandstand and the children’s programme Blue Peter are broadcast. STD (Subscriber Trunk Dialling) is introduced for direct telephone dialling and the state opening of Parliament is televised for the first time.

There are severe storms in the South. There are more dense fogs in the year that closes the decade – 1959 – more CND rallies as well. Juke Box Jury, chaired by David Jacobs, is shown for the first time on BBC television. Cliff Richards releases Living Doll and the first Mini goes on sale. The Conservatives win for the third time with a majority of 100 seats. Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club opens in Soho, as does the M1.

CND marches also mark the beginning of the new decade – 1960. The Shadows release Apache, whilst The Beatles perform their first shows in Hamburg, Germany. In the ‘Battle of Beaulieu’, fans of Trad. jazz come to blows with those who prefer modern jazz at a festival. Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker is produced at the Arts Theatre, London. The Beyond the Fringe satirical review has its first performance in Edinburgh. Nigeria gains independence. The first Traffic Wardens appear on the streets and there are record rainfalls in the north. Saturday Night, and Sunday Morning – the first of the social-realist plays – appears in film and Penguin is cleared of obscenity for publishing D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The farthing is no longer legal tender, and the last man is called up for National Service by conscription. The first episode of Coronation Street is broadcast by ITV television. For the first time, an Archbishop of Canterbury (Church of England) meets with a Pope in the Vatican. In 1961, a Soviet spy ring is discovered in London. The Beatles perform at the Cavern Club for the first time and the TV series The Avengers is screened. George Formby dies. Black and white five-pound notes are no longer legal tender and betting shops are legalised. The word ‘homosexual’ is used for the first time in a British film, whilst birth control pills become available on the National Health. The Taste of Honey film deals with both. Still further CND protests in Trafalgar Square – 1,300 people are arrested.

The Sunday Times becomes the first paper with a Sunday colour supplement in 1962, and Z Cars, University Challenge, and Steptoe and Son are broadcast by the BBC. Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev dance together in Giselle and the new Coventry Cathedral is consecrated. The Beatles play their first session at Abbey Road and their first engagement as John, Paul, George and Ringo (also their first TV appearance). They also release the Love Me Do single. The Tornados record Joe Meek’s Telstar in honour of the satellite that made live public transatlantic television broadcasts possible. The Rolling Stones make their debut at the Marquee – 165 Oxford Street, London. There are further race riots in Dudley, the Midlands and further smogs in London. The first James Bond film – Dr No – is released, as is David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. Britain agrees to buy the Polaris nuclear missile defense system from the USA and to develop the supersonic aircraft Concorde with France. Marilyn Monroe is found dead. The second Vatican Council is announced.

There is a ‘big freeze’ in Britain with no frost-free nights between December 22nd and 5th March 1963 the birth-rate subsequently rises. In March this year, The Beatles release their first LP Please, Please Me; it stays in the charts for some thirty weeks, only being displaced from number one by their second LP With The Beatles in November of the same year. Meanwhile, Cliff Richards releases the film Summer Holiday. Charles de Gaulle vetoes Britain’s membership of the Common Market, and there are more CND marches at Aldermarston. The Profumo Affair erupts when it is discovered that John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War, and a soviet official had been sharing the same call girl. Richard Beeching announces huge cuts to the British rail service. A huge expansion in Higher Education is recommended by the Robbins Report. She Loves You by The Beatles is number one, and later I Want To Hold Your Hand. The Great Train Robbery takes place. The National Theatre, newly formed under Lawrence Olivier, opens with Hamlet staring Peter O’Toole. Alex Douglas Hume replaces Harold Macmillan as Prime Minister. The American President John F Kennedy is shot dead. The final man is released from National Service. The BBC series Dr Who is broadcast for the first time, and later the Daleks make their inaugural appearance.

Top of the Pops begins in 1964 on the BBC. £10 bank notes are issued for the first time, and there are power disputes. The pirate radio station Radio Caroline opens offshore and there are violent clashes between mods and rockers at Clacton Beach. Joe Orton’s black comedy Entertaining Mr Sloane premieres in the New Arts Theatre in London. The new modern chic furniture store Habitat opens in London’s Fulham Rd. Granada TV begins broadcasting 7 Up (a documentary series that charts – returning every seven years – the progress through life of a group of seven year olds from mixed social backgrounds). The BBC airs Match of the Day, and the Beatles release Hard Day’s Night. Winston Churchill retires from the House of Commons. The Kinks have a hit single with You Really Got Me. The Labour Party wins the general election with a majority of five seats and with Harold Wilson as its leader. There are power union strikes. Moors murders missing persons are registered. The Trades Union Congress attempts an alliance with employers in Productivity, Prices and Incomes. In December, Donald Campbell sets the world speed record on water. The Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies opens in Birmingham University.

1965 and Winston Churchill dies, whilst Sir Stanley Matthews plays his final first division football game. The Prime Ministers of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 year. Both the Greater London Council and the Confederation of British Industry are founded. Comprehensive Schools are supported by Tony Crossland and Edward Heath is elected by the Conservative Party. The Beatles release the film Help! and Thunderbirds – a new form of puppet animation – is televised for the first time. Jacqueline DuPre releases Elgar’s Cello Concerto. The word ‘fuck’ is spoken for the first time on British TV and Mary Whitehouse founds the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association. Mary Quant introduces the mini skirt. Meanwhile, cigarette advertising is banned on the BBC. James Bond’s Aston Martin is the most popular Corgi toy and 70 mph becomes the legal speed limit on British roads.

England wins the football World Cup in 1966, the year in which ‘the decade exploded’, according to Jon savage. In fact, the World cup itself was stolen by an unknown and then rediscovered by the dog Pickles. The broadcaster Richard Dimbleby dies at age 52. The Beatles are ‘more popular than Jesus’, comments John Lennon in an interview published by The Evening Standard. They go straight to number one with the song Paperback Writer and release the LP Revolver. They also play their very last live concert in San Francisco, USA. The boutique, Granny Takes a Trip, opens in the Kings Road. The sitcom Till Death Us Do Part is broadcast for the first time on the BBC. London is described as ‘swinging’ by Time magazine. The first credit card is issued by Barclays. Harold Wilson calls a General election to increase his one seat majority, which he succeeds in doing – the majority rising to 96. A ‘pay freeze’ is announced. The ‘docudrama’ play Cathy Come Home is shown on the BBC. The Moors Murderers Ian Brady and Myra Hindley are found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. 144 people, including 116 children die when a coal mine spoil tip collapses in Aberfan, South Wales. Centre Point, London’s 32 floor office building is completed and remains empty. The M1, M4 (including the Severn Bridge) and M6 motorways are expanded.

Milton Keynes is formally designated a New Town in 1967 and the Queen Elizabeth Hall opened. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones are arrested on drugs charges, and the Polaris nuclear submarine launched. Parliament decides to nationalise 90% of the British Steel Industry. The first North Sea Oil is pumped ashore and the super tanker, the Torrey Canyon, runs aground between Lands End and the Isles of Scilly. Puppet on a String, sung by Sandy Shaw, wins the European Song Contest and Jim Hendrix sets fire to his guitar for the first time, resulting in him being hospitalised. The Beatles release Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Pink Floyd, Piper at the Gates of Dawn. The Beatles also open an Apple shop in London’s Carnaby Street. The first cash machine is installed by Barclays and the first TV programmes broadcast in colour. The Prisoner TV series is shown. The BBC Home and Third radio channels become Radio 4 and 3, whilst the Light splits between Radios 1 and 2. Francis Chichester completes his single-handed non-stop sailing around the world. Homosexuality becomes decriminalised and abortion legal on a number of counts. Concorde – the Anglo-French supersonic aircraft – is unveiled in Toulouse, France.

‘I’m Backing Britain’ is endorsed by Harold Wilson as a slogan for workers to work longer hours for no extra pay in 1968 as Labour’s popularity slumps in opinion polls. Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber is premiered in London and the Kinks release The Village Green Preservation Society. First and Second Class post are created. Martin Luther King’s killer is arrested in London. Enoch Powell makes his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech. The Beatles animated film Yellow Submarine is released and there are floods in SE England. The American musical Hair brings nudity to the London stage and Dad’s Army is aired for the first time by the BBC.